Ray Peat’s article about Salt is included below in its entirety.

All discussions above Peat’s are based on my own opinions and interpretations and what I have found useful for my own use as well as from feedback from many, many, many, many others.

Follow this link for more information about real food.

And follow this link for more information about the recommended few supplements.

In my notes, Peat suggests using untreated, unheated salt, white salt, about a teaspoon full per day as a supplement besides what’s found naturally in food.

I use powdered salt for my needs and always use a little extra of it since powdering the salt increases its volume. A measured teaspoon of powdered salt will be less overall salt than a granulated salt teaspoon full.

Peat has suggested splitting up the teaspoon amount into portions, or adding it to juice or water and sipped at during the day.

He thinks it helps many endocrine functions, as well as nerve electrical function, and muscle health, particularly heart health and thyroid function.

The body adapts to the additional salt after about 2 to 3 days. See Ray Peat books.

If at all possible to still find, (and it’s harder these days with various Country restrictions around trading and commerce), my most recommended salt is New Zealand sea salt.

I have found New Zealand sea salts are usually the most pristine, contaminant free salt type, as well as having the least amount of other excipients, minerals and metals that can be found in other earth or sea salts.

These “included” minerals and metals, especially iron which should be eliminated anywhere in your diet or supplements whenever possible, are not beneficial as the marketing proclaims, and a person could be over-medicating, over-supplementing themselves with dangerous heavy metals or other minerals by using salts or other single foods that are naturally or unnaturally adulterated with additional items.

I’ve been able to get it here so far (sometimes sold out). And here (the packaging looks a little different, but this coarse version is similar, also sometimes sold out).

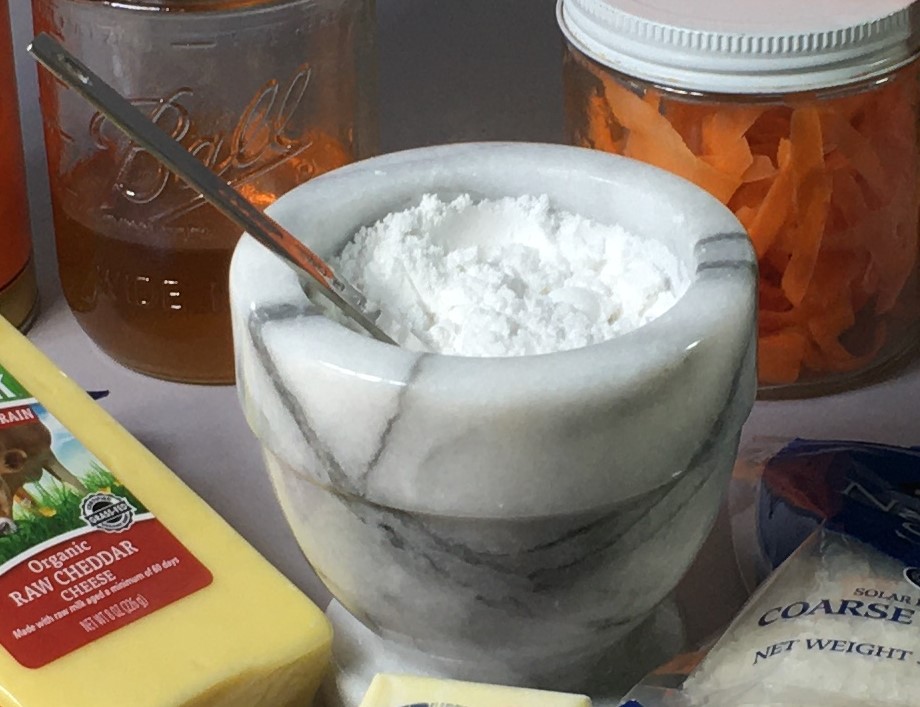

I like the coarse version because the larger salt pieces are easier to see and pick out any black impurity flakes. This is also why I started finely grinding it up myself, “powdering” it, years ago.

I have purchased the New Zealand salt as “fine” but it often is still rather coarse. It has no flow agent to it and can clump.

Some New Zealand salt in “fine” still also has a bit of brine to it and can be damp.

If New Zealand salt is not available, Celtic salt is a good choice but ONLY if you can find it white, NOT pink, not a color. Himalayan or Celtic salt that is a color, like pink, includes metals like iron, copper or other that you do NOT want to ingest on a long term or even short term basis.

If natural salts like these cannot be acquired, I have used plain white canning salt.

Canning salt has no additives, no anti-caking agents, no additional “nutrients” or “fortifications”.

HACK: I use an old coffee mill or the Bullet blender and I powder the dry salt very fine before use. The coarse version is the easiest to manage if you want to powder it.

Because natural salt has no flow agents, it can get lumpy. I use my thumb and forefinger to “un-lump” it, pinch it and sprinkle it on the food. When it’s powdered and I use my clean fingers to spread the salt instead of shaking off a spoon, it’s exceptionally easy to sprinkle the salt around the food.

I use measure spoons in it when I need to be more precise with quantity. But remember, the powdered salt will be slightly less salty, and just less salt overall even in the measure spoon.

But even the still damp fine salt will be ok to powder it. It was still a bit damp. I leave the finished salt out in a granite mortar bowl to use all day long.

Powdering the salt creates a gourmet type salt that tastes less salty but spreads the salt flavor around more evenly.

Natural salt will still clump even if powdered but if powdered finely enough, the salt is barely gritty and it’s easier to work into the diet often.

It’s easy enough to use, especially on the carrot salad, but on the eggs, in the potatoes, on the meat.

A R T I C L E

Salt, energy, metabolic rate, and longevity

In the 1950s, when the pharmaceutical industry was beginning to promote some new chemicals as diuretics to replace the traditional mercury compounds, Walter Kempner’s low-salt “rice diet” began to be discussed in the medical journals and other media. The diuretics were offered for treating high blood pressure, pulmonary edema, heart failure, “idiopathic edema,” orthostatic edema and obesity, and other forms of water retention, including pregnancy, and since they functioned by causing sodium to be excreted in the urine, their sale was accompanied by advising the patients to reduce their salt intake to make the diuretic more effective.

It was clear to some physicians (and to most veterinarians) that salt restriction, especially combined with salt-losing diuresis, was very harmful during pregnancy, but that combination became standard medical practice for many years, damaging millions of babies.

Despite numerous publications showing that diuretics could cause the edematous problems that they were supposed to remedy, they have been one of the most profitable types of drug. Dietary salt restriction has become a cultural cliché, largely as a consequence of the belief that sodium causes edema and hypertension.

Salt restriction, according to a review of about 100 studies (Alderman, 2004), lowers the blood pressure a few points. But that generally doesn’t relate to better health. In one study (3000 people, 4 years), there was a clear increase in mortality in the individuals who ate less salt. An extra few grams of salt per day was associated with a 36% reduction in “coronary events” (Alderman, et al., 1995). Another study (more than 11,000 people, 22 years) also showed an inverse relation between salt intake and mortality (Alderman, et al., 1997).

Tom Brewer, an obstetrician who devoted his career to educating the public about the importance of prenatal nutrition, emphasizing adequate protein (especially milk), calories, and salt, was largely responsible for the gradual abandonment of the low-salt plus diuretics treatment for pregnant women. He explained that sodium, in association with serum albumin, is essential for maintaining blood volume. Without adequate sodium, the serum albumin is unable to keep water from leaving the blood and entering the tissues. The tissues swell as the volume of blood is reduced.

During pregnancy, the reduced blood volume doesn’t adequately nourish and oxygenate the growing fetus, and the reduced circulation to the kidneys causes them to release a signal substance (renin) that causes the blood to circulate faster, under greater pressure. A low salt diet is just one of the things that can reduce kidney circulation and stimulate renin production. Bacterial endotoxin, and other things that cause excessive capillary permeability, edema, or shock-like symptoms, will activate renin secretion.

The blood volume problem isn’t limited to the hypertension of pregnancy toxemia: “Plasma volume is usually lower in patients with essential hypertension than in normal subjects” (Tarazi, 1976).

Several studies of preeclampsia or toxemia of pregnancy showed that supplementing the diet with salt would lower the women’s blood pressure, and prevent the other complications associated with toxemia (Shanklin and Hodin, 1979).

It has been known for many years that decreasing sodium intake causes the body to respond adaptively, increasing the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). The activation of this system is recognized as a factor in hypertension, kidney disease, heart failure, fibrosis of the heart, and other problems. Sodium restriction also increases serotonin, activity of the sympathetic nervous system, and plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 (PAI-1), which contributes to the accumulation of clots and is associated with breast and prostate cancer. The sympathetic nervous system becomes hyperactive in preeclampsia (Metsaars, et al., 2006).

Despite the general knowledge of the relation of dietary salt to the RAA system, and its application by Brewer and others to the prevention of pregnancy toxemia, it isn’t common to see the information applied to other problems, such as aging and the stress-related degenerative diseases.

Many young women periodically crave salt and sugar, especially around ovulation and premenstrually, when estrogen is high. Physiologically, this is similar to the food cravings of pregnancy. Premenstrual water retention is a common problem, and physicians commonly offer the same advice to cycling women that was offered as a standard treatment for pregnant women–the avoidance of salt, sometimes with a diuretic. But when women premenstrually increase their salt intake according to their craving, the water retention can be prevented.

Blood volume changes during the normal menstrual cycle, and when the blood volume is low, it is usually because the water has moved into the tissues, causing edema. When estrogen is high, the osmolarity of the blood is low. (Courtar, et al., 2007; Stachenfeld, et al., 1999). Hypothyroidism (which increases the ratio of estrogen to progesterone) is a major cause of excessive sodium loss.

The increase of adrenalin caused by salt restriction has many harmful effects, including insomnia. Many old people have noticed that a low sodium diet disturbs their sleep, and that eating their usual amount of salt restores their ability to sleep. The activity of the sympathetic nervous system increases with aging, so salt restriction is exacerbating one of the basic problems of aging. Chronically increased activity of the sympathetic (adrenergic) nervous system contributes to capillary leakage, insulin resistance (with increased free fatty acids in the blood), and degenerative changes in the brain (Griffith and Sutin, 1996).

The flexibility of blood vessels (compliance) is decreased by a low-salt diet, and vascular stiffness caused by over-activity of the sympathetic nervous system is considered to be an important factor in hypertension, especially with aging.

Pregnancy toxemia/preeclampsia involves increased blood pressure and capillary permeability, and an excess of prolactin. Prolactin secretion is increased by serotonin, which is one of the substances increased by salt restriction, but prolactin itself can promote the loss of sodium in the urine (Ibarra, et al., 2005), and contributes to vascular leakage and hypertension.

In pregnancy, estrogen excess or progesterone deficiency is an important factor in the harmful effects of sodium restriction and protein deficiency. A deficiency of protein contributes to hypothyroidism, which is responsible for the relative estrogen excess.

Protein, salt, thyroid, and progesterone happen to be thermogenic, increasing heat production and stabilizing body temperature at a higher level. Prolactin and estrogen lower the temperature set-point.

The downward shift of temperature and energy metabolism in toxemia or salt deprivation tends to slow the use of oxygen, increasing the glycolytic use of sugar, and contributing to the formation of lactic acid, rather than carbon dioxide. In preeclampsia, serum lactate is increased, even while free fatty acids are interfering with the use of glucose.

One way of looking at those facts is to see that a lack of sodium slows metabolism, lowers carbon dioxide production, and creates inflammation, stress and degeneration. Rephrasing it, sodium stimulates energy metabolism, increases carbon dioxide production, and protects against inflammation and other maladaptive stress reactions.

In recent years, Weissman’s “wear-and-tear” theory of aging, and Pearl’s “rate of living” theory have been clearly refuted by metabolic studies that are showing that intensified mitochondrial respiration decreases cellular damage, and supports a longer life-span.

Many dog owners are aware that small dogs eat much more food in proportion to their size than big dogs do. And small dogs have a much greater life expectancy than big dogs, in some cases about twice as long (Speakman, 2003).

Organisms as different as yeasts and rodents show a similar association of metabolic intensity and life-span. A variety of hamster with a 20% higher metabolic rate lived 15% longer than hamsters with an average metabolic rate (Oklejewicz and Daan, 2002).

Individuals within a strain of mice were found to vary considerably in their metabolic rate. The 25% of the mice with the highest rate used 30% more energy (per gram of body weight) than the 25% with the lowest metabolic rate, and lived 36% longer (Speakman, et al., 2000).

The mitochondria of these animals are “uncoupled,” that is, their use of oxygen isn’t directly proportional to the production of ATP. This means that they are producing more carbon dioxide without necessarily producing more ATP, and that even at rest they are using a considerable amount of energy.

One important function of carbon dioxide is to regulate the movement of positively charged alkali metal ions, such as sodium and calcium. When too much calcium enters a cell it activates many enzymes, prevents muscle and nerve cells from relaxing, and ultimately kills the cell. The constant formation of acidic carbon dioxide in the cell allows the cell to remove calcium, along with the small amount of sodium which is constantly entering the cell.

When there is adequate sodium in the extracellular fluid, the continuous inward movement of sodium ions into the resting cell activates an enzyme, sodium-potassium ATPase, causing ATP to break down into ADP and phosphate, which stimulates the consumption of fuel and oxygen to maintain an adequate level of ATP. Increasing the concentration of sodium increases the energy consumption and carbon dioxide production of the cell. The sodium, by increasing carbon dioxide production, protects against the excitatory, toxic effects of the intracellular calcium.

Hypertonic solutions, containing more than the normal concentration of sodium (from about twice normal to 8 or 10 times normal) are being used to rescuscitate people and animals after injury. Rather than just increasing blood volume to restore circulation, the hypertonic sodium restores cellular energy production, increasing oxygen consumption and heat production while reducing free radical production, improves the contraction and relaxation of the heart muscle, and reduces inflammation, vascular permeability, and edema.

Seawater, which is hypertonic to our tissues, has often been used for treating wounds, and much more concentrated salt solutions have been found effective for accelerating wound healing (Mangete, et al., 1993).

There have been several publications suggesting that increasing the amount of salt in the diet might cause stomach cancer, because countries such as Japan with a high salt intake have a high incidence of stomach cancer.

Studies in which animals were fed popular Japanese foods–“salted cuttlefish guts, broiled, salted, dried sardines, pickled radish, and soy sauce”–besides a chemical carcinogen, showed that the Japanese foods increased the number of tumors. But another study, adding only soy sauce (with a salt content of about 18%) to the diet did not increase the incidence of cancer, in another it was protective against stomach cancer (Benjamin, et al., 1991). Several studies show that dried fish and pickled vegetables are carcinogenic, probably because of the oxidized fats, and other chemical changes, and fungal contamination, which are likely to be worse without the salt. Animals fed dried fish were found to have mutagenic urine, apparently as a result of toxic materials occurring in various preserved foods (Fong, et al., 1979).

Although preserved foods develop many peculiar toxins, even fresh fish in the diet have been found to be associated with increased cancer risk (Phukan, et al., 2006).

When small animals were given a milliliter of a saturated salt solution with the carcinogen, the number of tumors was increased with the salt. However, when the salt was given with mucin, it had no cancer promoting effect. Since the large amount of a saturated salt solution breaks down the stomach’s protective mucus coating, the stomach cells were not protected from the carcinogen. Rather than showing that salt causes stomach cancer, the experiments showed that a cup or more of saturated salt solution, or several ounces of pure salt, shouldn’t be ingested at the same time as a strong carcinogen.

Some studies have found pork to be associated with cancer of the esophagous (Nagai, et al., 1982), thyroid (Markaki, et al., 2003), and other organs, but an experiment with beef, chicken, or bacon diet in rats provides another perspective on the role of salt in carcinogenesis. After being given a carcinogen, rats were fed meat diets, containing either 30% or 60% of freeze-dried fried beef, chicken, or bacon. Neither beef nor chicken changed the incidence of precancerous lesions in the intestine, but the incidence was reduced by 12% in the animals on the 30% bacon diet, and by 20% in rats getting the diet with 60% bacon. Salt apparently made the difference.

Other protective effects of increased sodium are that it improves immunity (Junger, et al., 1994), reduces vascular leakiness, and alleviates inflammation (Cara, et al., 1988). All of these effects would tend to protect against the degenerative diseases, including tumors, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease. The RAA system appears to be crucially involved in all kinds of sickness and degeneration, but the protective effects of sodium are more basic than just helping to prevent activation of that system.

A slight decrease in temperature can promote inflammation (Matsui, et al., 2006). The thermogenic substances–dietary protein, sodium, sucrose, thyroid and progesterone–are antiinflammatory for many reasons, but very likely the increased temperature itself is important.

A poor reaction to stress, with increased cortisol, can raise the body temperature by accelerating the breakdown and resynthesis of proteins, but adaptive resistance to stress increases the temperature by increasing the consumption of oxygen and fuel. In the presence of increased cortisol, abdominal fat increases, along with circulating fatty acids and calcium, as mitochondrial respiration is suppressed.

When mice are chilled, they spontaneously prefer slightly salty water, rather than fresh, and it increases their heat production (Dejima, et al., 1996). When rats are given 0.9 per cent sodium chloride solution with their regular food, their heat production increases, and their body fat, including abdominal fat, decreases (Bryant, et al., 1984). These responses to increased dietary sodium are immediate. Part of the effect of sodium involves regulatory processes in the brain, which are sensitive to the ratio between sodium and calcium. Decreasing sodium, or increasing calcium, causes the body’s metabolism to shift away from thermogenesis and accelerated respiration.

Regulating intracellular calcium by increasing the production of carbon dioxide is probably a basic mechanism in sodium’s protection against inflammation and excitatory cell damage and degeneration.

Cortisol’s suppression of mitochondrial respiration is closely associated with its ability to increase intracellular calcium. Cortisol blocks the thermogenic effects of sodium, allowing intracellular calcium to damage cells. With aging, the tissues are more susceptible to these processes.

The thermogenic effects of sodium can be seen in long-term studies, as well as short. A low-sodium diet accelerates the decrease in heat production that normally occurs with aging, lowering the metabolic rate of brown fat and body temperature, and increasing the fat content of the body, as well as the activity of the fat synthesizing enzyme (Xavier, et al., 2003).

Activation of heat production and increased body temperature might account for some of the GABA-like sedative effects of increased sodium. Increasing GABA in the brain increases brown fat heat production (Horton, et al., 1988). Activation of heat production by brown fat increases slow wave sleep (Dewasmes, et al., 2003), the loss of which is characteristic of aging. (In adult humans, the skeletal muscles have heat-producing functions similar to brown fat.)

Now that inflammation is recognized as having a central role in the degenerative diseases, the fact that renin, angiotensin, and aldosterone all contribute to inflammation and are increased by a sodium deficiency, should arouse interest in exploring the therapeutic uses of sodium supplementation, and the integrated use of all of the factors that normally support respiratory energy production, especially thyroid and progesterone. Progesterone’s antagonism to aldosterone has been known for many years, and the synthetic antialdosterone drugs are simply poor imitations of progesterone.

But the drug industry is interested in selling new drugs to block the formation and action of each of the components of the RAAS, rather than an inexpensive method (such as nutrition) to normalize the system.

REFERENCES

J Hum Hypertens. 2002 Dec;16(12):843-50. Salt supresses baseline muscle sympathetic nerve activity in salt-sensitive and salt-resistant hypertensives. Abrahão SB, Tinucci T, Santello JL, Mion D Jr.

Neuropharmacology. 1986 Jun;25(6):627-31. Activation of thermogenesis of brown fat in rats by baclofen. Addae JI, Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ, Stone TW.

Hypertension 25: 1144-1152, 1995: Low urinary sodium is associated with greater risk of myocardial infarction among treated hypertensive men. Alderman MH, Madhavan S, Cohen H, Sealey JE, Laragh JH

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I). Lancet 351: 781-785, 1998: Dietary sodium intake and mortality, Alderman MH, Cohen H, Madhavan S.

Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1982;4(7):1073-83. Aortic rigidity and plasma catecholamines in essential hypertensive patients. Alicandri CL, Agabiti-Rosei E, Fariello R, Beschi M, Boni E, Castellano M, Montini E, Romanelli G, Zaninelli A, Muiesan G.

Anesth Analg. 1989 Dec;69(6):714-20. Hypertonic saline solution-hetastarch for fluid resuscitation in experimental septic shock. Armistead CW Jr, Vincent JL, Preiser JC, De Backer D, Thuc Le Minh.

J Clin Invest. 1976 Feb;57(2):368-79. Thyroid thermogenesis. Relationships between Na+-dependent respiration and Na+ + K+-adenosine triphosphatase activity in rat skeletal muscle. Asano Y, Liberman UA, Edelman IS.

Experientia Suppl. 1978;32:199-203. Increased cell membrane permeability to Na+ and K+ induced by thyroid hormone in rat skeletal muscle. Asano Y.

Nephron 1986;44(1):70-4. Effect of sodium bicarbonate preloading on ischemic renal failure. Atkins JL Rats pretreated with sodium bicarbonate were functionally protected from the damage of bilateral renal artery occlusion.

Cancer Res. 1991 Jun 1;51(11):2940-2. Inhibition of benzo(a)pyrene-induced mouse forestomach neoplasia by dietary soy sauce. Benjamin H, Storkson J, Nagahara A, Pariza MW.

Am J Vet Res. 1990 Jul;51(7):999-1007. Effect of hypertonic vs isotonic saline solution on responses to sublethal Escherichia coli endotoxemia in horses. Bertone JJ, Gossett KA, Shoemaker KE, Bertone AL, Schneiter HL. “. . . cardiac output was increased and total peripheral resistance was decreased during the hypertonic, compared with the isotonic, saline trial.”

Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Sep;289(3):E429-38. Epub 2005 May 10. Long-term caloric restriction increases UCP3 content but decreases proton leak and reactive oxygen species production in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. Bevilacqua L, Ramsey JJ, Hagopian K, Weindruch R, Harper ME.

Int J Obes. 1984;8(3):221-31. Influence of sodium intake on thermogenesis and brown adipose tissue in the rat. Bryant KR, Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ.

Braz J Med Biol Res. 1988;21(2):281-3. Effect of hyperosmotic sodium chloride solution on vascular permeability and inflammatory edema in rats. Cara DC, Malucelli BE.

Experientia Suppl. 1978;32:25-32. Does cytoplasmic alkalinization trigger mitochondrial energy dissipation in the brown adipocyte? Chinet A, Friedli C, Seydoux J, Girardier L.

Am J Clin Nutr. 1993 Nov;58(5):608-13. Effects of infused sodium acetate, sodium lactate, and sodium beta-hydroxybutyrate on energy expenditure and substrate oxidation rates in lean humans. Chioléro R, Mavrocordatos P, Burnier P, Cayeux MC, Schindler C, Jéquier E, Tappy L.

Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006 Mar;16(2):148-55. High- or low-salt diet from weaning to adulthood: effect on body weight, food intake and energy balance in rats. Coelho MS, Passadore MD, Gasparetti AL, Bibancos T, Prada PO, Furukawa LL, Furukawa LN, Fukui RT, Casarini DE, Saad MJ, Luz J, Chiavegatto S, Dolnikoff MS, Heimann JC.

Reprod Sci. 2007 Jan;14(1):66-72. Orthostatic stress response during the menstrual cycle is unaltered in formerly preeclamptic women with low plasma volume. Courtar DA, Spaanderman ME, Janssen BJ, Peeters LL.

Neurosci Lett. 2003 Mar 27;339(3):207-10. Activation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis increases slow wave sleep in rat. Dewasmes G, Loos N, Delanaud S, Dewasmes D, Géloën A.

Fiziol Cheloveka. 2005 Nov-Dec;31(6):97-105. Cardioprotection by aldosterone receptor antagonism in heart failure. Part I. The role of aldosterone in heart failure. Dieterich HA, Wendt C, Saborowski F.

Appetite. 1996 Jun;26(3):203-19. Cold-induced salt intake in mice and catecholamine, renin and thermogenesis mechanisms. Dejima Y, Fukuda S, Ichijoh Y, Takasaka K, Ohtsuka R.

Brain Res Bull. 1984 Apr;12(4):355-8. Effects of hyperprolactinaemia on core temperature of the rat. Drago F, Amir S.

Hypertension. 2006 Dec;48(6):1103-8. Epub 2006 Oct 23. Influence of salt intake on renin-angiotensin and natriuretic peptide system genes in human adipose tissue. Engeli S, Boschmann M, Frings P, Beck L, Janke J, Titze J, Luft FC, Heer M, Jordan J.

Am J Nephrol. 2000 Jan-Feb;20(1):37-41. Hyponatremia in acute-phase response syndrome patients in general surgical wards. Ferreira da Cunha D, Pontes Monteiro J, Modesto dos Santos V, Araújo Oliveira F, Freire de Carvalho da Cunha S.

Int J Cancer. 1979 Apr 15;23(4):542-6. Preserved foods as possible cancer hazards: WA rats fed salted fish have mutagenic urine. Fong LY, Ho JH, Huang DP.

Br J Pharmacol. 2004 Jan;141(1):152-62. Epub 2003 Dec 8. Changes in rectal temperature and ECoG spectral power of sensorimotor cortex elicited in conscious rabbits by i.c.v. injection of GABA, GABA(A) and GABA(B) agonists and antagonists. Frosini M, Valoti M, Sgaragli G.

3: J Physiol (Paris). 1972 Oct;65:Suppl:234A. [Brown fat, sodium pump and thermogenesis] [Article in French] Girardier L, Seydoux J.

J Comp Neurol. 1996 Jul 29;371(3):362-75. Reactive astrocyte formation in vivo is regulated by noradrenergic axons. Griffith R, Sutin J.

Nutr Cancer. 1990;14(2):127-32. Gastric lesions in rats fed salted food materials commonly eaten by Japanese. Hirono I, Funahashi M, Kaneko C, Ogino H, Ito M, Yoshida A.

Neuropharmacology. 1988 Apr;27(4):363-6. Opposing effects of activation of central GABAA and GABAB receptors on brown fat thermogenesis in the rat. Horton RW, LeFeuvre RA, Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ.

Gen Pharmacol. 1988;19(3):403-5. Chronic inhibition of GABA transaminase results in activation of thermogenesis and brown fat in the rat. Horton R, Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ.

Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001 Apr;280(4):H1591-601. Hypertonic saline-dextran suppresses burn-related cytokine secretion by cardiomyocytes. Horton JW, Maass DL, White J, Sanders B.

Obes Rev. 2007 May;8(3):231-51. Animal and human tissue Na,K-ATPase in normal and insulin-resistant states: regulation, behaviour and interpretative hypothesis on NEFA effects. Iannello S, Milazzo P, Belfiore F.

Tohoku J Exp Med. 1988 Jul;155(3):285-94. The absence of correlation between Na in diet duplicates and stomach cancer mortality in Japan. Ikeda M, Nakatsuka H, Watanabe T.

J Clin Invest. 1986 Nov;78(5):1311-5. Sodium regulation of angiotensinogen mRNA expression in rat kidney cortex and medulla. Ingelfinger JR, Pratt RE, Ellison K, Dzau VJ.

Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1987 Sep;1(3):665-93. The contracted plasma volume syndromes (relative polycythaemias) and their haemorheological significance. Isbister JP.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007 Apr;27(4):799-805. Epub 2007 Jan 18. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation promotes vascular cell calcification. Jaffe IZ, Tintut Y, Newfell BG, Demer LL, Mendelsohn ME.

Circ Shock. 1994 Apr;42(4):190-6. Hypertonic saline enhances cellular immune function. Junger WG, Liu FC, Loomis WH, Hoyt DB.

Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1984;6(9):1543-58. Low sodium diet augments plasma and tissue catecholamine levels in pithed rats. Kaufman LJ, Vollmer RR.

Placenta. 2007 Aug-Sep;28(8-9):854-60. Hypoxia and lactate production in trophoblast cells. Kay HH, Zhu S, Tsoi S.

Am J Dis Child. 1991 Sep;145(9):985-90. Oral water intoxication in infants. An American epidemic. Keating JP, Schears GJ, Dodge PR.

J Cardiol. 2007 Apr;49(4):187-91. Thermal therapy improves left ventricular diastolic function in patients with congestive heart failure: a tissue doppler echocardiographic study. Kisanuki A, Daitoku S, Kihara T, Otsuji Y, Tei C.

J Physiol. 2001 Sep 1;535(Pt 2):601-10. Thermogenesis induced by intravenous infusion of hypertonic solutions in the rat. Kobayashi A, Osaka T, Inoue S, Kimura S.

Gan No Rinsho. 1990 Feb;Spec No:275-84. [Stomach cancer mortality and nutrition intake in northern Japan–especially on relation to sodium chloride] Komatsu S, Fukao A, Hisamichi S. “There is a big difference on the stomach cancer (SC) mortality between the north-western and the north-eastern parts of Honshu….” “1. There are no significant differences on salt intake between the north-western and the north-eastern parts of Honshu. 2. Intake of milk and dairy products is negatively related to SC. 3. Intake of animal protein is negatively related to CVD.”

Exp Gerontol. 2004 Mar;39(3):289-95. The effect of aging and caloric restriction on mitochondrial protein density and oxygen consumption. Lambert AJ, Wang B, Yardley J, Edwards J, Merry BJ. “However, the respiration rate of mitochondria from brown adipose tissue (BAT) of CR animals was approximately three-fold higher compared to mitochondria from fully fed controls.”

Fertil Steril. 1981 Apr;35(4):403-5. Elevated prolactin levels in oral contraceptive pill-related hypertension. Lehtovirta P, Ranta T, Seppälä M.

Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1979;92:203-7. High renin in heart failure: a manifestation of hyponatremia. Levine TB, Cohn JN, Vrobel T, Franciosa JA.

Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [A]. 1975 Nov;83(6):661-8. The effect of angiotensin infusion, sodium loading and sodium restriction on the renal and cardiac adrenergic nerves. Ljungqvist A.

Circ Shock. 1986;20(4):311-20. Fluid resuscitation with hypertonic saline in endotoxic shock. Luypaert P, Vincent JL, Domb M, Van der Linden P, Blecic S, Azimi G, Bernard A.“Intravascular pressures were similar in the two groups, but cardiac output, stroke volume, and oxygen consumption were significantly higher in the hypertonic group.”

Eur J Cancer. 2003 Sep;39(13):1912-9. The influence of dietary patterns on the development of thyroid cancer. Markaki I, Linos D, Linos A.),

Poult Sci. 1983 Feb;62(2):263-72. The relationship of altered water/feed intake ratios on growth and abdominal fat in commercial broilers. Marks HL, Washburn KW.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Jul;79(13):4239-41. Action of food restriction in delaying the aging process. Masoro EJ, Yu BP, Bertrand HA. Thus, the data in this report do not support the concept that food restriction slows the rate of aging by decreasing the metabolic rate.

J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2006 Jul;18(3):189-93. Mild hypothermia promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine production in monocytes. Matsui T, Ishikawa T, Takeuchi H, Okabayashi K, Maekawa T.

J Trauma. 1996 Sep;41(3):439-45. Resuscitation of uncontrolled liver hemorrhage: effects on bleeding, oxygen delivery, and oxygen consumption. Matsuoka T, Wisner DH. “Animals in the HS group had significantly higher oxygen extraction ratios at the conclusion of the experiment.”

Am J Hypertens. 2003 Jan;16(1):92-4. DASH-sodium trial: where are the data? McCarron DA. Editorial

Kidney Int. 2005 Oct;68(4):1700-7. Prolactin, a natriuretic hormone, interacting with the renal dopamine system. Ibarra F, Crambert S, Eklöf AC, Lundquist A, Hansell P, Holtbäck U.

Hypertens Pregnancy. 2006;25(3):143-57. Increased sympathetic activity present in early hypertensive pregnancy is not lowered by plasma volume expansion. Metsaars WP, Ganzevoort W, Karemaker JM, Rang S, Wolf H.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006 Mar-Apr;8(3-4):548-58. Mitochondrial H2O2 production is reduced with acute and chronic eccentric exercise in rat skeletal muscle. Molnar AM, Servais S, Guichardant M, Lagarde M, Macedo DV, Pereira-Da-Silva L, Sibille B, Favier R.

Am J Hypertens. 1991 May;4(5 Pt 1):410-5. Salt restriction lowers resting blood pressure but not 24-h ambulatory blood pressure. Moore TJ, Malarick C, Olmedo A, Klein RC.

J Surg Res. 1987 Jul;43(1):37-44. Hypertonic saline resuscitates dogs in endotoxin shock. Mullins RJ, Hudgens RW.

J Physiol. 1971 Sep;217(2):381-92. Changes in body temperature of the unanaesthetized monkey produced by sodium and calcium ions perfused through the cerebral ventricles. Myers RD, Veale WL, Yaksh TL.

Nutr Cancer. 1982;3(4):257-68. Relationship of diet to the incidence of esophageal and stomach cancer in Japan. Nagai M, Hashimoto T, Yanagawa H, Yokoyama H, Minowa M.

Brain Res. 2002 Dec 13;957(2):271-7. Suppression of sodium pump activity and an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration by dexamethasone in acidotic mouse brain. Namba C, Adachi N, Liu K, Yorozuya T, Arai T.

Oklejewicz, M. and Daan, S. (2002). Enhanced longevity in tau mutant Syrian hamsters, Mesocricetus auratus. J. Biol. Rhythms 17, 210-216.

Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004 Aug;287(2):R306-13. Cold-induced thermogenesis mediated by GABA in the preoptic area of anesthetized rats. Osaka T.

Nutr Cancer 1998;32(3):165-73. Effect of meat (beef, chicken, and bacon) on rat colon carcinogenesis. Parnaud G, Peiffer G, Tache S, Corpet DE.

J Gastroenterol. 2006 May;41(5):418-24. Dietary habits and stomach cancer in Mizoram, India. Phukan RK, Narain K, Zomawia E, Hazarika NC, Mahanta J.

Ukr Biokhim Zh. 1980 Jan-Feb;52(1):36-9. [Corticosteroid hormone effect on oxygen consumption of rat brain and hippocampus mitochondria and homogenates] Podvigina TT.

Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1977 Feb;6(4-5):327-31. Lack of thyroid hormone effect on activation energy of NaK-ATPase. Rahimifar M, Ismail-Beigi.

Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2004 Nov;1(1):42-7. Mechanisms of disease: local renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems and the pathogenesis and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Re RN. “Accumulating evidence has made it clear that not only does the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) exist in the circulation where it is driven by renal renin, but it is also active in many tissues-and likely within cells as well.”

Public Health. 1988 Nov;102(6):513-6. Salt and hypertension–a dangerous myth? Robertson JS.

Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002 Oct;59(10):1714-23. Opposite actions of testosterone and progesterone on UCP1 mRNA expression in cultured brown adipocytes. Rodriguez AM, Monjo M, Roca P, Palou A.

Reproduction. 2006 Feb;131(2):331-339. Remodeling and angiotensin II responses of the uterine arcuate arteries of pregnant rats are altered by low- and high-sodium intake. St-Louis J, Sicotte B, Beausejour A, Brochu M.

Crit Care Med. 1991 Jun;19(6):758-62. Management of hyponatremic seizures in children with hypertonic saline: a safe and effective strategy. Sarnaik AP, Meert K, Hackbarth R, Fleischmann L.

J Appl Physiol. 1979 Jul;47(1):1-7. Temperature regulation and hypohydration: a singular view. Senay LC Jr. “Body temperatures of exercising humans who have been denied water are elevated when compared to hydrated controls.”

Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2000 Mar-Apr;16(2):94-105. Overnutrition in spiny mice (Acomys cahirinus): beta-cell expansion leading to rupture and overt diabetes on fat-rich diet and protective energy-wasting elevation in thyroid hormone on sucrose-rich diet. Shafrir E.

D.R. Shanklin, and Jay Hodin. Maternal Nutrition and Child Health, C.C.Thomas, 1979,

J Hypertens. 1993 Dec;11(12):1381-6. Effect of dietary salt restriction on urinary serotonin and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid excretion in man. Sharma AM, Schorr U, Thiede HM, Distler A.

The Journal of Membrane Biology, 211(1), 2006, pp. 35-42(8). Hypertonic Saline Attenuates Colonic Tumor Cell Metastatic Potential by Activating Transmembrane Sodium Conductance Shields C, Winter D, Geibel J, O’Sullivan G, Wang J, Redmond, H.

Surgery, Volume 136, Issue 1, Pages 76-83. Hypertonic saline impedes tumor cell–endothelial cell interaction by reducing adhesion molecule and laminin expression. Shields C, Winter D, Wang J, Andrews E, Laug W, Redmond H.

FEBS Lett. 1998 Sep 11;435(1):25-8. Glucocorticoids decrease cytochrome c oxidase activity of isolated rat kidney Mitochondria. Simon N, Jolliet P, Morin C, Zini R, Urien S, Tillement JP.

Metabolism. 1977 Feb;26(2):187-92. Osmotic control of the release of prolactin and thyrotropin in euthyroid subjects and patients with pituitary tumors. Sowers JR, Hershman JM, Showsky WR, Carlson HE, Park J.

Journal of Experimental Biology 2005, 208, 1717-1730, Body size, energy metabolism, and lifespan, Speakman, JR.

FASEB J. 14, A757 (2000). Living fast and dying old. Speakman, J. R., et al..

Am J Hypertens. 2002 Aug;15(8):683-90. PAI-1 in human hypertension: relation to hypertensive groups. Srikumar N, Brown NJ, Hopkins PN, Jeunemaitre X, Hunt SC, Vaughan DE, Williams GH.

J Appl Physiol. 1999 Sep;87(3):1016-25. Effects of oral contraceptives on body fluid regulation. Stachenfeld NS, Silva C, Keefe DL, Kokoszka CA, Nadel ER.

J Appl Physiol. 1999 Sep;87(3):1016-25. Effects of oral contraceptives on body fluid regulation. Stachenfeld NS, Silva C, Keefe DL, Kokoszka CA, Nadel ER.

Exp. Gerontol. 2, 173-182 (1967). Relation of lifespan to brain weight, body weight and metabolic rate among inbred mouse strains. Storer, J. B.

Am J Pathol 2002 Nov;161(5):1773-81. Aldosterone-induced inflammation in the rat heart: role of oxidative stress. Sun Y, Zhang J, Lu L, Chen SS, Quinn MT, Weber KT.

Circ Res. 1976 Jun;38(6 Suppl 2):73-83. Hemodynamic role of extracellular fluid in hypertension. Tarazi RC. “Plasma volume is usually lower in patients with essential hypertension than in normal subjects.”

Gann. 1976 Apr;67(2):223-9. Protective effect of mucin on experimental gastric cancer induced by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine plus sodium chloride in rats. Tatematsu M, Takahashi M, Hananouchi M, Shirai T, Hirose M.

Aging Cell. 2007 Jun;6(3):307-17. Expansion of the calcium hypothesis of brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease: minding the store. Thibault O, Gant JC, Landfield PW.

Life Sci. 1990;47(25):2317-22. Pharmacological evidence for involvement of the sympathetic nervous system in the increase in renin secretion produced by a low sodium diet in rats. Tkacs NC, Kim M, Denzon M, Hargrave B, Ganong WF.

J Trauma. 1992 Jun;32(6):704-12; discussion 712-3. Effects of hypertonic saline dextran resuscitation on oxygen delivery, oxygen consumption, and lipid peroxidation after burn injury. Tokyay R, Zeigler ST, Kramer GC, Rogers CS, Heggers JP, Traber DL, Herndon DN.

Pflugers Arch. 1976 Jun 22;363(3):219-22. Is the chemomechanical energy transformation reversible? Ulbrich M, Rüegg JC.

Experientia 1971 Jan 15;27(1):45-6. Stretch induced formation of ATP-32P in glycerinated fibres of insect flight muscle. Ulbrich M, Ruegg JC

Front Biosci. 2007 Jan 1;12:2457-70. Maternal-fetal metabolism in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. von Versen-Hoeynck FM, Powers RW.

Br J Nutr. 2005 May;93(5):575-9. The effects of drinks made from simple sugars on blood pressure in healthy older people. Visvanathan R, Chen R, Garcia M, Horowitz M, Chapman I.

Clin Cardiol. 1980 Oct;3(5):348-51. Sympathetic nervous system activity during sodium restriction in essential hypertension. Warren SE, Vieweg WV, O’Connor DT.

Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2004 Jul;1(2):51-6. Efficacy of aldosterone receptor antagonism in heart failure: potential mechanisms. Weber KT.

J Hypertens. 1996 Dec;14(12):1461-2. Is salt-sensitivity of blood pressure a reproducible phenomenon-commentary. Weinberger MH. Hypertension Research Center, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis 46202, USA.

J Clin Invest. 1983 Apr;71(4):916-25. Stimulation of thermogenesis by carbohydrate overfeeding. Evidence against sympathetic nervous system mediation. Welle S, Campbell RG.

Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986 Jan 18;292(6514):168-70. Treatment of hyponatraemic seizures with intravenous 29.2% saline. Worthley LI, Thomas PD. “Five patients with severe hyponatraemia and epileptiform seizures were given 50 ml of 29.2% saline (250 mmol) through a central venous catheter over 10 minutes to control seizures rapidly, reduce cerebral oedema, and diminish the incidence of permanent neuronal damage. The saline controlled seizures in all patients, increasing the mean serum sodium concentration by 7.4 (SD 1.14) mmol(mEq)/l and decreasing the mean serum potassium concentration by 0.62 (0.5) mmol(mEq)/l.”

Metabolism. 2003 Aug;52(8):1072-7. Dietary sodium restriction exacerbates age-related changes in rat adipose tissue and liver lipogenesis. Xavier AR, Garófalo MA, Migliorini RH, Kettelhut IC.“Taken together, the data indicate that prolonged dietary sodium restriction exacerbates normal, age-related changes in white and BAT metabolism.”

Geriatr Nurs. 1997 Mar-Apr;18(2):87-8. Is salt restriction dangerous for elders? Yen PK.

Copyright 2007. Raymond Peat, P.O. Box 5764, Eugene OR 97405. All Rights Reserved. www.RayPeat.com

Not for republication without written permission.